We sometimes lose sight of the fact that a process, and process development ie. writing procedures, is a means to an end, not an end in itself.

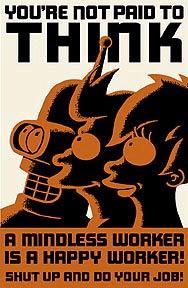

One thing a process can do, is free people, who have the capability and desire, to perform activities requiring skill, judgment, knowledge and adaptive thinking, while allowing people not so inclined, or capable, to perform certain discrete tasks defined by a process.

If a task is discrete and can be defined by a series of actions leading to an end it doesn't particularly matter who does it, where it's done or in some cases if a human needs to perform the task at all.

This is all good. It makes things more efficient and allows businesses to employ people with varying degrees of skill, knowledge and judgement while paying appropriate wages for work based on the ability to proceduralize a set of rules for getting that work done, as well as the complexity of the procedure and the potential implications of failing to follow the procedure.

Even a complete procedure (a written process) doesn't eliminate the need to employ skilled workers, with appropriate pay, to perform certain tasks.

For example the steps required to fill the milkshake machine at McDonald's or many other tasks where workers can be interchanged, require no particular skill or judgement, and the pay is in accord.

The steps required to paint a car could be recorded but to accomplish that work requires a degree of skill and the pay is in accord.

The steps required to land an airplane with an engine out, or shutdown a nuclear powerplant in the event of a potential core meltdown can be recorded but we don't pay McD or bodyshop wages because the potential implication for mistakes are loss of human life, and more importantly even though the "steps" can be recorded we can't take the human element out of the equation and ensure safety...yet.

Thus we begin to step into the grey area of following a process vs. thinking.

It's interesting to think of a seemingly simple task like tying your shoe, or a tie, and try to write a process for how to do that. Even with pictures and good instructions it can be hard to master those tasks.

If we step from a simple task involving only inananimate objects to any task involving human interaction we are immediately faced with the challenge of predicting how a particular human will react to our procedure/script/recipe.

Generally any attempt to script human interaction is doomed to failure. We are quick to pick up an attempt to mimic human interaction using a set of rules, for example the millisecond it takes to recognize a telemarketer's call.

Our human nature is to avoid the false (artificial) in preference to the true (real) as a matter of survival. In human interaction, being true - being real, is the basis for trust...without trust we have nothing (or maybe in the case of some business operations we have to write a procedure? or for a marriage prepare a pre-nuptial agreement?)

High value professional occupations are not conducive to being proceduralized, although they may involve following many procedures, the distinction is the ability to think, to consider, to integrate facts and intuition, work on a case by case basis, in real time, in an adaptive way - "what works best right now?", "how can we get this done given our current set of constraints?"

I don't want a doctor to operate on me, or a lawyer to represent me, using a script, but I want him or her to know the procedures. What I pay them the big bucks for is their ability to think.

Ditto for any professional occupation...

of course there are exceptions to any rule.